As outlined in part I, there are different aspects of an API you need to take into account when working on the documentation: the dataset as a whole, the API calls and response structure, RDF properties and classes, provenance information. In this post we want to share how we approached their documentation for the two services lobid-resources and lobid-organisations, using lobid-organisations as primary example.

High-level documentation of the dataset

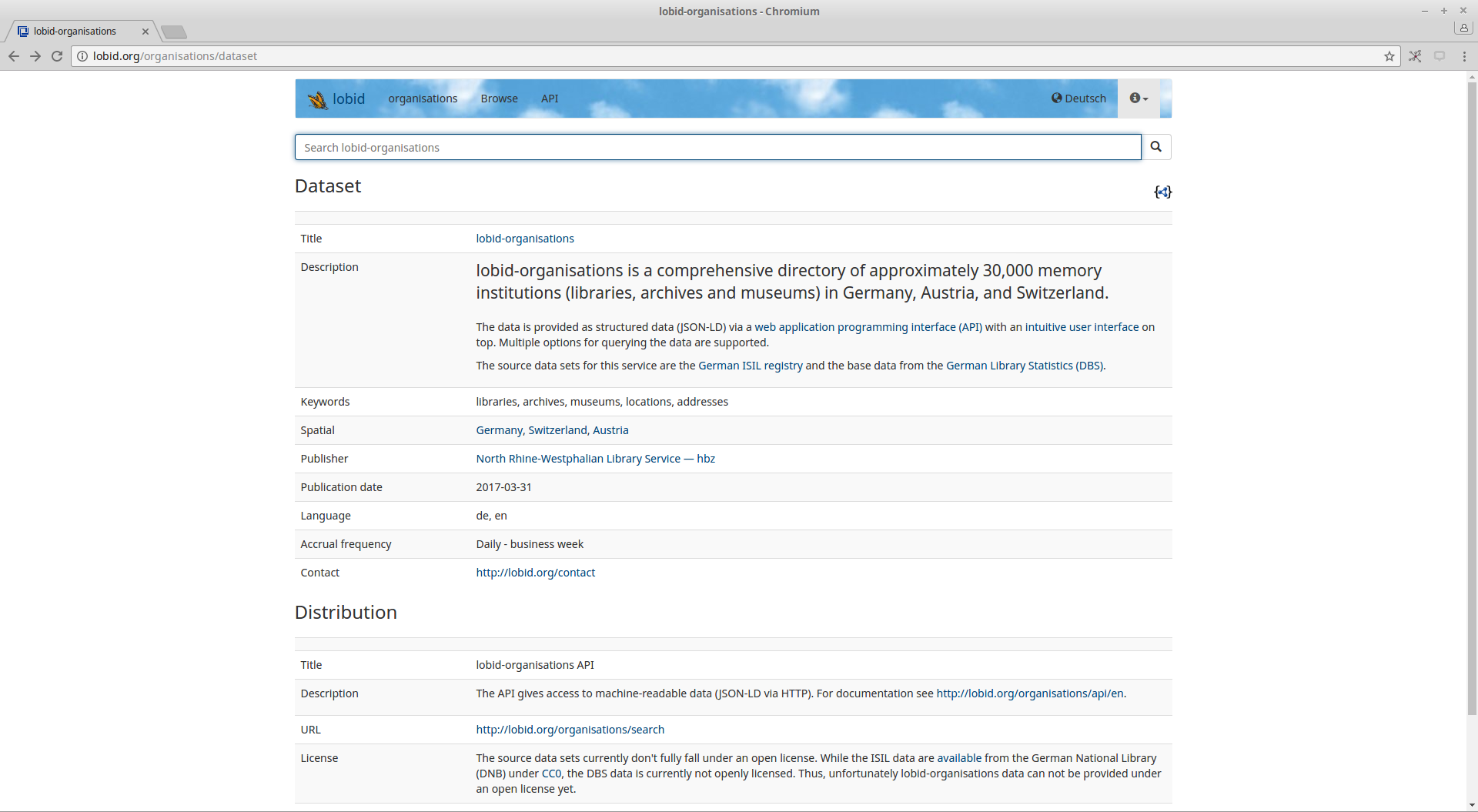

To give people (as well as machines) a quick overview over the dataset that is provided via the API, we mostly followed the W3C’s Data on the Web Best Practices recommendation. The result is a JSON-LD file describing the dataset, as well as a human-readable HTML version of the same information. Note that unlike the W3C recommendation, which uses DC Terms for its examples, we decided to use schema.org properties and classes where possible.

HTML-version of the lobid-organisations data set description

Documenting the API

The API documentation (lobid-organisations, lobid-resources) introduces basic API request concepts by providing example queries, expands these with some advanced queries on nested fields, and provides details for tricky cases like querying for URLs (which require escaping of special characters). For a full reference on the supported query syntax, we link to the relevant Lucene documentation.

The documentation describes the supported response content types and provides samples for requesting them. We provide complete documentation on using the API to build an autocomplete functionality, including an embedded example in the documentation page.

For the lobid-organisations documentation, we finally describe its specific functionality, like location based queries, CSV export, and OpenRefine reconciliation support.

Documentation by example

When we try to get an understanding of a schema and how it is used, we quickly find ourselves looking out for examples. But examples are often secondary parts of documentation, if given at all. It is common practice to use what can be called a “descriptive approach” of documenting a vocabulary or an application profile by listing elements in tables – often contained within a PDF – and describing their different aspects in various columns.

schema.org is an exception in that it tries to provide examples. But even in schema.org the examples are an appendix to the description and sometimes even missing (e.g. it is hard to learn about how to use the publication property and the publication event class).

We believe that examples should be an integral part of documentation, while we deem page-long tables listing elements of a metadata schema as not very helpful and rather annoying. So we thought about how to put the example in the center of documentation following the bold claim that “All documentation should be built around examples”.

Using web annotation tools for API documentation

A blog post on API documentation from 2010 says about examples:

In addition to sample code, having HTTP, XML, and JSON samples of your request and response is important. However, samples only are not sufficient. In addition, you need a description that explains the purpose of the call and you need a table that explains each element. We recommend a table with columns for Name, Type, Description, and Remarks.

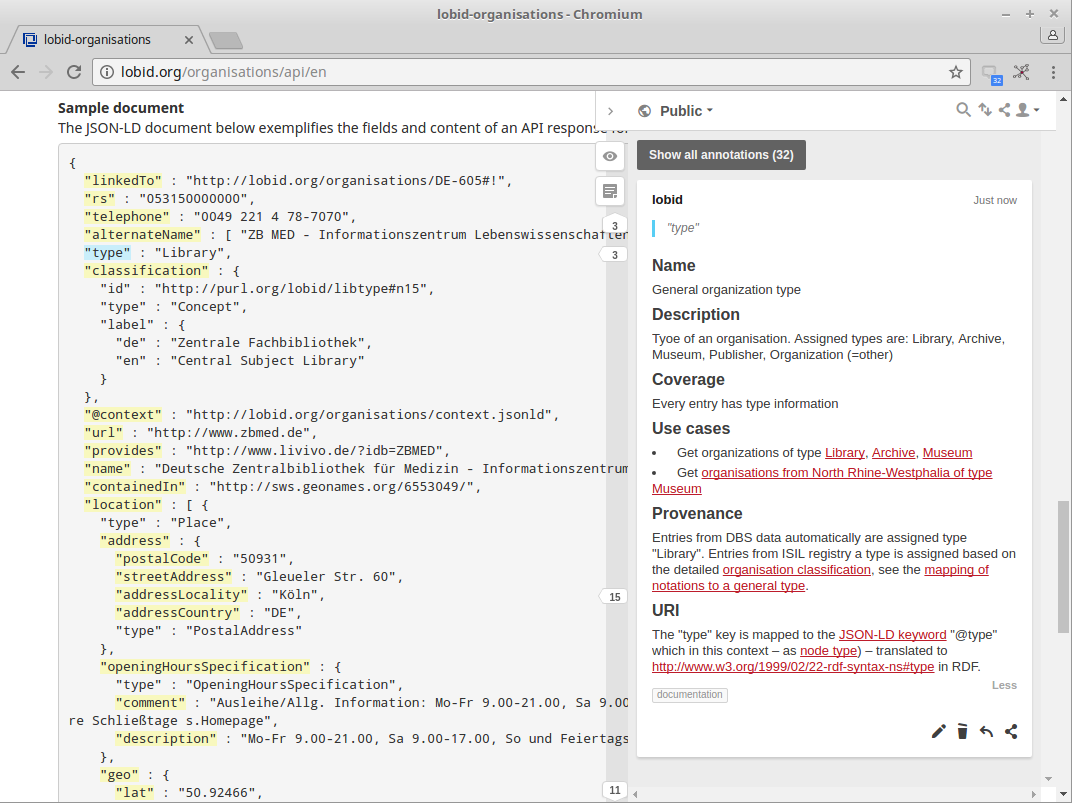

Agreed, that samples alone are not sufficient, but do we really need a table describing each element of our data? When putting the example first, why not attach the structured descriptive data (name, description, etc.) to the example? Today, this is quite easy to achieve with web annotation tools. So we took production examples of our JSON-LD data and annotated them with hypothes.is.1 For lobid-organisations, it was enough to annotate one example file. In order to cover most of the fields used in the lobid-resources data, we had to annotate different kinds of examples (book, periodical, article, series volume).

We chose to annotate each JSON key adding the following information:

- Name: a human-readable name for the field

- Description: a short description of the information in the field

- Coverage: the number of resources that have information in this field (Here, you will often find example URLs on how to query the field.)

- Use cases: example use cases on what the information from the field can be used for, along with example queries

- URI: the RDF property the JSON key is mapped to

- Provenance: information about the source data fields the information is derived from

While the first two information points (name and description) and the URI can be found in every annotation, the others are not (yet) available for every field. We try to develop a better feeling on how to use the API by adding lots of example queries in the documentation, especially in the “Coverage” and “Use cases” section.

At http://lobid.org/organisations/api you can see documentation by annotation in action.2 Just go to the JSON-LD section and click on one of the highlighted JSON keys. The hypothes.is side bar will open with information about the data element.

Example annotation on the “type” key

Benefits

The examples taken for documentation should at best be live data from production. Thus, if something changes on the data side, the example – and with it the documentation – automatically updates. For example, if the value of a field changes, the documentation will automatically show the new data. If a specific field was removed in the data, and therefore in the example, the corresponding hypothes.is annotation becomes an “orphan”.

We hope that this documentation approach based on annotation of examples is more useful and more fun than the traditional descriptive approach. It should give people an intuitive and interactive interface for exploring and understanding the data provided by the lobid API. If any questions remain, API users can easily ask questions regarding specific parts of the documentation by replying to a hypothes.is annotation and we will automatically be notified via email.

We are curious what you think about this documentation approach. Let us know by adding an annotation to the whole post (“page note”) or by annotating specific parts.

1 At first we planned to directly annotate the JSON files as provided via lobid (e.g. this) but people would only be able to see the annotations when using the hypothes.is Chrome plugin. Another option is hypothes.is’ via service but it does not support annotation of text files. Thus, we decided to embed the JSON content on-the-fly in a HTML page, and add the hypothes.is script to the page.

2 There is also a German version, and the lobid-resources documentation solely exists in German.

Comments? Feedback? Just add an annotation with hypothes.is.